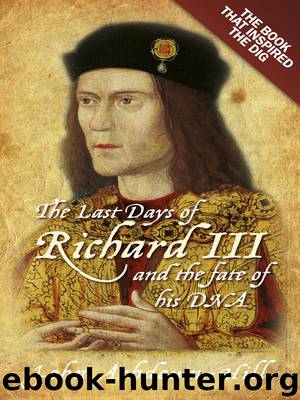

The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA by John Ashdown-Hill

Author:John Ashdown-Hill

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Publisher: The History Press

Published: 2013-03-31T21:00:00+00:00

12

‘Here Lies the Body’1

When Henry VIII dissolved the religious houses of England, the fate of the burials within the monastic and conventual churches varied. Occasionally, surviving relatives took steps to rescue their loved ones. In such rare instances coffined bodies – or even entire tombs – were moved elsewhere. In other cases, empty tomb superstructures alone may have been salvaged without their accompanying bodies, and re-erected as cenotaphs. This seems to have occurred in the case of three tombs from Earls Colne Priory, which once housed the de Veres (Earls of Oxford). As we shall see in greater detail below, King Henry VIII himself had the body of his sister, Mary, moved from Bury St Edmunds Abbey to St Mary’s church in the same town. The Earl of Essex had the monuments and remains of his father and grandparents moved from Beeleigh Abbey to the parish church at Little Easton in Essex. Later, following the death of the third Howard Duke of Norfolk, his heirs transferred the remains of his father and grandfather (the two preceding Howard dukes) from Thetford Priory to Framlingham church. The bodies and tombs of the Howards’ Mowbray forebears, however, were left behind in the ruins of Thetford Priory, and theirs was the more common fate by far. The superstructure of their tombs subsequently pillaged and lost, the mortal remains of the Mowbrays still lie buried where they were originally interred.

In the case of Richard III there were no close relatives on hand to rescue his remains when the Leicester Greyfriars were expelled in 1538. The superstructure of his tomb probably remained for a while in the roofless ruin of the choir. Indeed, it is even remotely possible that Richard’s tomb effigy survives to this day, having eventually been salvaged and relocated in another church, like the de Vere tombs from Earls Colne.2 As for Richard’s body, as recent excavation at the Greyfriars site has proved, it simply remained lying where the friars had buried it in 1485. Even before the excavation, the available evidence strongly suggested that this was so. In due course the friary site was acquired by the Herrick family. Robert Herrick, one-time mayor of Leicester, constructed a house and laid out a garden on the eastern part of the site, where once the choir of the priory church had stood. Here in 1612 Christopher Wren (future dean of Windsor and father of the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral), who was then tutor to Robert Herrick’s nephew, saw ‘a handsome stone pillar, three foot high’, bearing the inscription: ‘Here lies the body of Richard III, some time King of England’.3 This pillar had been erected by Robert Herrick when he redeveloped the site in order to preserve the location of Richard’s grave. What subsequently happened to this ‘handsome stone pillar’ is unknown. ‘It may not have survived the taking of Leicester by the Royalists [during the English Civil War], when desperate fighting took place near St Martin’s Church [Cathedral] which was immediately north of the Grey Friars’ grounds.

Download

The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA by John Ashdown-Hill.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26602)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23084)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16853)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13336)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7140)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5515)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5095)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4962)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4814)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4801)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4478)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4354)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4274)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4198)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4109)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4031)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3965)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3640)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3467)